After almost a year without a downpour, a procession of powerful Pacific winds is overseen at Northern California this weekend, potentially giving rise to as much as a foot of drizzle and up to three feet of sleet in the Sierra Nevada. Supercharged by a distinctive atmospheric river form, the downpours could direct to flash floods and hazardous residue flows in a wide swath of the region already overpowered by recent wildfires.

With each consecutive hurricane, the precipitation potential gains, peaking with probably an extraordinary category 5 atmospheric river event on Sunday. An atmospheric river summed as a category 4 or a 5 is worthy of generating considerable downpour amounts over three or more days, potentially to surpass 10-15% of a regular year’s drizzle in some areas,” explained Marty Ralph, administrator of the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes at UC San Diego.

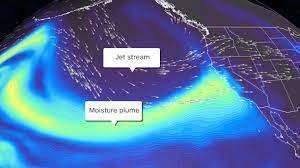

Atmospheric rivers are a thin band of concentrated vapor in the atmosphere meandering more than two miles above the sea. They can move as vapor, having more than 20 times the moisture that the Mississippi River has as a liquid. By Monday morning approaches, the advancement of winds could plunge as much as 8 to 12 inches of downpour in portions of Northern California and expand another 1 to 3 feet of sleet to the elevated Sierra. For a region afflicted by drought, a foot of downpour is too much, too rapidly, and too quick. It will probably direct to a runoff, flash floods, and debris flow in burn scar regions.

A race to deter debris spurts

Burn scars — the charred geography — abandoned after the Dixie Fire, near Mount Lassen, and the Caldor Fire, not distant from South Lake Tahoe, stay vulnerable to flash floods and residue gush. This fatal, fast-moving mass composed of liquid, stone, dirt, and greenery can wreak devastation on populations downstream, eradicating residences and infrastructure. These geologic dangers are a consequence of scorched earth, which can be as water repellent as pavement. Rainfall that would otherwise be absorbed by the soil now can run off quickly after a wildfire.

The Cal Fire-led Watershed Emergency Response Team has been gearing up ahead of the heavy rains, assessing and identifying the areas most susceptible to post-fire hazards, such as debris flows, flooding, and rockfall.

“Weathering is very challenging to manage on the most precipitous and most critically heated parts of a blackened space, and these usually occur in the most prominent danger to life, protection and resources,” states Lynnette Round, Cal Fire information officer.

“The sections of interest are where values-at-risk (homes, roadways, etc) are under steep fields baked at average to dirt burn austerity,” states Round. “For the Dixie Fire, this is essentially along the Highway 70 passage and lots of Indian Valley and Genesee Valley. For the Caldor Fire, this would be accompanying parts of the Highway 50 passage, and the low-lying regions of the Cosumnes River,” Round continues. In January 2018, just weeks after the Thomas Fire burned the hills of Santa Barbara County, people residing beneath hillsides in burn fields were destroyed by various debris flows after a powerful January hurricane wrecked the district.